Designing a Bass Guitar

Published 27 Oct 2024

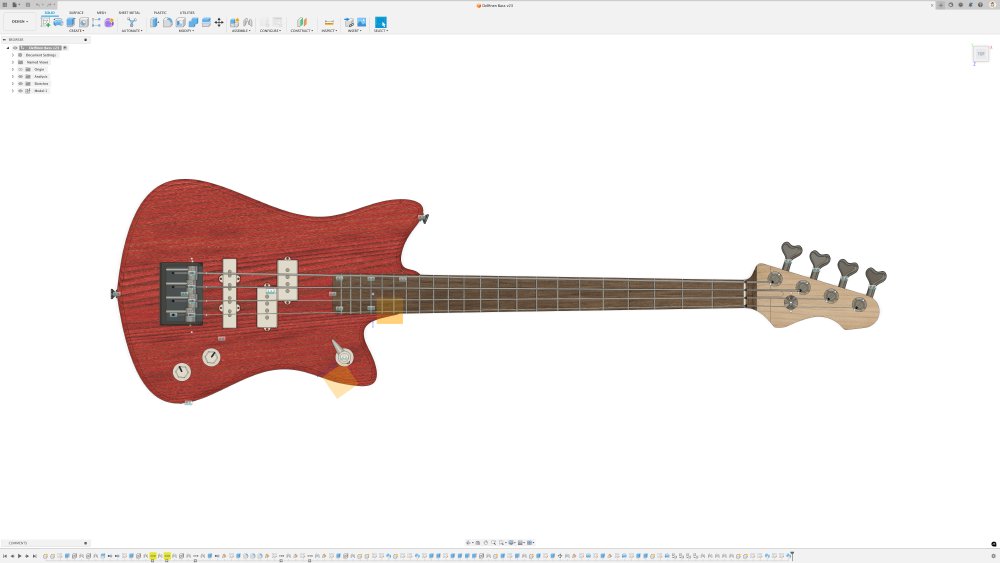

It’s been a couple of months since I’ve been able to get into the workshop, which has happened before, but it’s always a little hard to get back into the swing of things. Mostly I’ve been dragging my heels on getting back into doing design work, of which I have a bunch to do. It’s all felt quite overwhelming knowing where to start, but thankfully a conversation with a couple of friends, Patrick and Jon, gave me an obvious gentle way back in, and so I grabbed at it, and have spent the last couple of weekends designing a bass guitar:

This isn’t the first time I’ve tried to design a bass guitar, but the first time I tried to leap into designing one in the style of Älgen, in all its 3D-printed, headless uniqueness, which was trying to run before I could walk. Not only have never built a bass guitar before, I’ve also not really spent any extended time playing one to make me familiar with the instrument. I can play a few bass lines, but I’ve never tried to be a bass player. So this time the rule was: simplify. What are the fundamental parts to a bass guitar? What is the minimal I need to make a good playable bass. With the aim that I can then build that instrument quickly (for me) and work out what I got wrong and build on from there.

Where to begin

My friend was talking about how he liked the Fender Mustang Bass, which is a short-scale bass guitar:

This in turn is derived from their Mustang Guitar, of which I have built several guitars based on that design in the past, like this one:

Hopefully you can see the resemblance.

I said the Mustang Bass is a short-scale bass guitar, so what does that mean? On a guitar the scale-length is the distance from the nut at the top of the neck to the saddles on the bridge, i.e., the length of an open string. Most Fender guitars have a 25.5" scale-length, but the Mustang Guitar is notably shorter, at 24". Similarly, Fender’s most popular bass guitars, the Precision Bass and the Jazz Bass have a scale-length of 34", whereas the Mustang Bass has a scale-length of 30", making it quite short for a bass. Indeed, you can get baritone guitars at 28".

I have to confess, personally I’m not that into the Mustang Bass looks, on account of the overly large headstock, but I do quite like the idea of a compact and light bass guitar, and so I got interested in what could I make in this space, particularly given my history of making Mustang-like guitars in the past. One of my current models, Delfinen, is sort of my own personal take on the Mustang guitar:

So the question became: what would a Delfinen Bass be like?

What is the difference between a bass and a guitar?

A common question I get asked is what is it that makes a regular guitar and a bass guitar different? All the stringed instruments operate on the same principle, and a guitar, a bass, and a ukulele are all the same instrument effectively, just optimised for different parts of the musical scale (i.e., different frequency ranges). The longer a string you have, or the lower tension you have on a string, the lower the note it’ll produce is. But no matter how you set it up, it’s always the case that if you press down half way along the string (12-fret on those instruments with frets) you get a note one octave higher - so the mechanism for changing notes once you have established the behaviour with the strings “open” is the same.

So a bass guitar has a longer neck to let you run strings one octave lower than a regular guitar, assuming you have both in standard tuning. But length isn’t the only variable, which is why you can have a 24" and a 25.5" scale-length guitar in the same standard tuning, as the notes also depend on string-tension. This is also why you can have a baritone guitar that’s somewhere between bass and regular guitar, but at a scale-length close to that of a short-scale bass: they have strings at different tensions.

As a final thing, I’ve only talked about fretted instruments here, but the same principe does also apply to the classical stringed instruments, which brings us to the fun fact that a bass guitar and a double bass are tuned to make the same notes. This is I assume why bass guitars typically have 4 strings rather than 6 like a guitar, as they were playing the same music, just in a more convenient and easily amplifiable package.

All of which is saying that in theory, for my target of a 30" scale-length bass guitar, if I want to build it based on my 24" scale-length guitar, I can just hop into my CAD tool, tell it to scale everything up by a factor of 1.25, and we’re done! Thanks for reading this post, I’ll be sure to… oh, wait.

Whilst technically that would work, that would make for a somewhat unwieldily instrument, and so bass guitars are designed to try keep the convenience of the guitar format, but have quite a few adjustments to allow for longer the scale-length. For instance, on a standard guitar, you’ll see there is typically a good amount of material between the bottom of the guitar and the bridge, which is there to help with ergonomics, but if you look at a bass guitar, the bridge typically has been moved to the very bottom of the guitar, filling in that extra space, trying to keep the overall length of the instrument down (cf how big a double bass is, where they did kinda just scale up the common design more closely - though this example sent to me by Jon shows that you can try scale them too!).

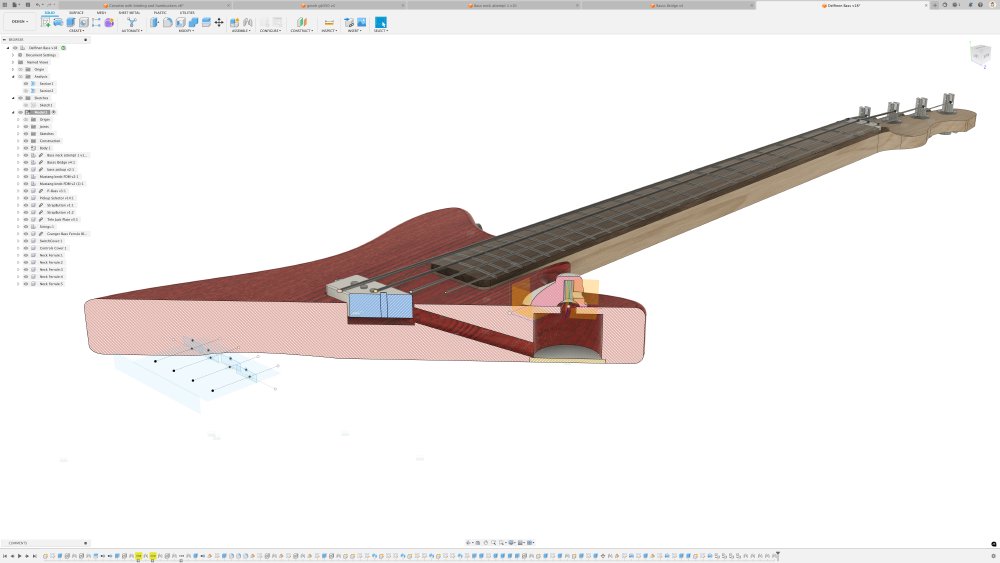

That distance moved though isn’t proportional to the part of the string that is not over the fretboard on a regular guitar, so if we kept the body size the same and the neck-joint in the same place, we’d lose a bunch of frets: about five frets on Delfinen. Given the shape of the body is defined for comfort of holding the instrument, we don’t want to shrink that too much, so instead the neck-joint has to move further into the body, as shown by this very early version of my design:

Although we still have the full 22 frets, those top few we saved are not really that useful now, as they’re now much harder to reach, so the cut-away on the right-hand side of the neck has to be made more pronounced to let the player reach them with their left hand (flipped if you’re building a left-handed guitar). In doing this you can’t just remove material in one place and leave everything else on the body as is; well, technically you can and it’ll work, but visually it’ll almost certainly look odd, and so other lines on the body need to be adjusted to maintain the visual balance of the design. As a result Delfinen Bass is slightly more angular than its sibling, as I try to balance not shrinking the body overall yet providing access to those higher frets.

I suspect I still need to take a bit more out of my current design iteration, but it’s a lot better now than before I modified it, and before I go too wild I want to make this and see how it balances.

At the other end of the guitar, the headstock is made slightly bigger to accommodate the fewer, but considerably chonkier, tuners (it also thicker by a few millimetres for the same reason). I have to confess, I really don’t like how much Fender oversized the headstock on the Mustang Bass pictured above, and so I was a little cautious with mine, and we’ll see how it looks once I make the prototype. Again, I had to change the profile shape as just scaling up my regular design did look weird, particularly as the fretboard width at the nut is narrower, down from 42mm to 38mm on account of fewer strings: so you need a bigger headstock but a smaller joining area with the rest of the neck; this really adds to the weirdness in my mind if you just try scale things without updating them, and so I had a play visually until I think I’m happy, but the only way to tell will be to build it. I’ve not left any room for branding on the headstock, but I’ll figure that out once I have a good design, not before: I suspect this consideration is why the Fender one looks so ugly to me, as it was scaled more than technically necessary to ensure they had a place to stick the logo.

Finally, a quick look at the rear, where there’s nothing too unexpected: access for the electronics, a ferrule block of anchoring the strings, and you can see the longer neck-pocket reflected in the location of the screw ferrules for anchoring it on.

The belly carve comes close to the neck bolts, but that’s something that I hand carve anyway, so I’m not worried about them being that close in actual production. Relatedly, you can also see one of my guilty secrets: I never model the neck properly in CAD :) Given I carve it by hand and the transition is variable in quite a few ways, I’ve never braved trying to recreate all that in CAD, particularly as I never will benefit from that as I don’t use CNC. Don’t judge me too hard - it’s efficiency and not laziness I swear!

Pickups and all that Jazz (and Precision)

In general, bass-guitarists seem to be more open to unusual things than regular guitarists. Whilst I do think the guitar scene has become more accepting of new designs and new technology, there still is a strong sense of traditional being better in the guitar world. But in doing research for this, aided by lots of great suggestions from bass-playing friends, I get the sense that the bass world is more open to both unusual designs and electronics. Not that traditional bass is shunned, but both points in the space seem to exist together, and that is something that I find quite exciting.

As a case in point, I was introduced to the amazing genre-spanning Mohini Dey:

The bass guitar she plays is clearly a more modern design, far removed from the old Fender designs I’ve talked about so far: through neck, exotic wood patterns, etc. But in addition to being visually unconventional, it’s functionally unconventional in terms of the electronics and pickups. In this interview she talks about how this helps her get the sounds she needs for different styles whilst on the road without having to cart around lots of other bits of kit to do so:

It seems in general active-pickups, where you use a weaker magnet with a built-in pre-amp in the guitar, which are much less common for general guitar, are quite popular option for bass guitar: again, the bass world seems to have plenty of room for both styles. This is definitely something I’m interested in getting into, given my background is as a technologist, but for my Delfinen Bass I’m going to keep it traditional, and use passive pickups.

Why go for the old world when I’ve just been getting excited about the new world? It’s because the risky part of this project is whether the overall design is a good instrument or not, and I want to get that evaluated quickly. To enable that I’m going to use electronics like that I use in my guitar builds, as I know what I’m doing there. Once I know that the overall shape and style works, then I can play more.

The one thing that I was worried about by the pickup placement, which I’ve based on existing popular models, is the gap between the neck pickup and the cavity made to house the pickup selector rotary-switch. Normally I drill this using an extra long drill bit, but given the extended gap here, I was concerned I’d not be able to get the drill bit at a shallow enough angle to reach all the way without it fouling on some other part of the body or exiting too early. If not, then it’s easy to solve by using a two-piece body where the front face of the guitar is a different bit of wood from the back, and then all the wiring channels can be internal; this is something I did with Verkstaden and think I’ll probably switch to generally for my “normal” guitar builds. But it adds a bunch of time to the build process, and not what I want for a quick prototype.

So, as I always do, I modelled the long drill holes in Fusion to see if I could get an angle from the neck pickup pocket to the cavity for the selector as I’d normally do it that would work:

Just about! It’s a little tight: I’ve modelled it so the drill bit clears the far side of the pickup cavity by a couple of millimeters, and it still exits quite close to the edge of the control cavity. But I should get away with it. It is close enough though that I suspect I might 3D-print a guide jig this time to help give me a better chance of success.

On the topic of pickups, I was wondering how people route out the tight fitting pockets for bass pickups when not using a pick-guard. On the Fender Mustang Bass above you can see the pickup is mounted into the plastic pick-guard, and so they can cut a square cavity under there that’s big enough, but when you just mount them into the front of the guitar like this, corners present a challenge, as they’re a smaller radius than that of the router-bit you’d use to cut the hole.

I’m far from the first person to try this, so I went looking at how others do it, and found this great explainer from Stew Mac guitar tools:

The trick is before you route out the cavity, you use a small drill bit to drill the corners, and then you use the larger router bit for bulk. What I particularly like about this technique is that it both works by hand as they do here, and you can do the same trick with a CNC-router (if your machine supports drilling, I know not all do).

I realise that for both the above issues I could make my design even simpler if I just used a pick-guard, which goes against my opening guiding principle of “simplify”. But I think I’ve taken quite a deliberate stance against pick-guards, as I think they work against the maintainability of the instrument (requiring the strings off to do any adjustments to electronics). But I guess the joy of doing it this way is also if I mess it up then I can just put a pick-guard on there and say I meant it that way ;)

Summary

So after a couple of days of research and CAD design, I feel I’m ready to order some materials and give the Delfinen Bass a go.

I’ve very happy with where this has come. Would I liked to do more fancy things with it like I do with my guitars? Yes, I would. But if there’s one recurring theme of this blog is that I regularly strike out to do too much on new designs and then get lost in the weeds: the binding on Delfinen, the painting on Verkstaden, etc. I think it’s the point of custom instrument building to push into directions not afforded by off-the-shelf guitars, but one has to start somewhere, so for this instrument I’ll try, for once, to stick to executing something simple well, and then move up from there.